John Pagano, Ph.D., OTR/L

Overview Description

Participation in consistent restraint and seclusion reduction efforts is an important component of the practice of school occupational therapy practitioners. Consistent efforts to reduce restraint and seclusion are important at the school, classroom, small group and individual intervention level. Restraint reduction is a priority for schools, demonstrates the unique value of OT, expands its use of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (de Korte et al., 2021) and increases consultation with other school professionals (Welch & Poltajko, 2016). Because of the importance of reducing school restraint and seclusion for administrators, teachers and parents as well as the higher rates of use of these practices for students with special needs (Verret et al., 2019), collaborative efforts to reduce seclusion and restraint can expand the scope of practice of school occupational therapy (Benson et al., 2015; Frolek Clark et al., 2020).

Promote Mental Wellness Across Contexts

Consistency across school disciplines as well as Tier 1 (school), Tier 2 (small group), and Tier 3 (individual occupational therapy) interventions are important for reducing the incidences of restraint and seclusion of students with complex behavior challenges (e.g., Autism Spectrum Disorders, developmental, Traumatic Brain Injury mental health, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity and/or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). Expanded involvement of school OT practitioners through use of a work load model can help facilitate the reduction of school restraint and seclusion.

- Involvement of school OT practitioners in developing bulletin boards, school climate initiatives, staff/parent education, lunch room procedures, and structured playgrounds.

- Effective communication, positive relationships, and greater participation in IEP meetings with parents and educational staff can facilitate collaboration in reducing restraint and seclusion as well as improve parent and school staff perceptions of school OT services (Benson et al., 2015).

- Increased participation by OT practitioners in adapting potentially challenging environments to prevent behavioral difficulties and help reduce the use of seclusion and restraint. Examples of school OT initiatives could involve reducing extraneous noise levels of math classes (Kinnealey et al., 2015), encouraging appropriate socialization in the lunch room (Bazyk et al., 2018), and increasing playground structure.

- OT involvement in leading or co-leading social skills groups that improve the interpersonal functioning of students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (de Korte et al., 2021), cognitive disabilities, ADHD, and typical functioning (Wyman & Claro, 2019).

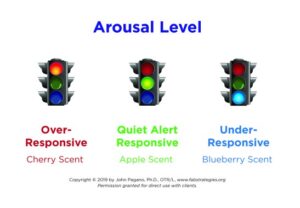

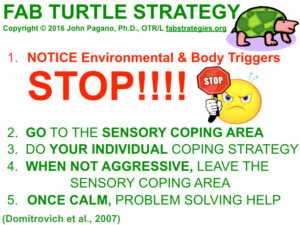

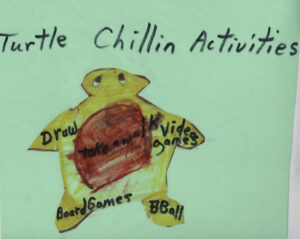

- Because students with behavioral problems show significantly increased difficulties with sensory processing disorders (Dellapiazza et al., 2019; Green et al., 2019; Benarous et al., 2020) school OT practitioners can add unique value through their use of sensory coping areas and teaching arousal level regulation strategies that help reduce restraint and seclusion for students with complex behavioral challenges (Verret et al., 2019; Caldwell et al., 2014). Promoting self-control through teaching arousal level recognition and regulation appears to increase self-control and normalize neurological development in students with fetal alcohol syndrome (Soh et al., 2015).

- Occupational therapy staff consultative and direct services using clinical reasoning to provide individualized adaptive equipment (e.g., sensory brushes, weighted blankets/vests, OT balls, Play-Doh) for students with mental health challenges can help significantly reduce aggression, restraint and seclusion in students with sensory and mental health challenges (Ashburner et al., 2014; Caldwell et al., 2014).

Prevent Further Existing Symptoms

Applied Behavior Support (Oakes et al., 2018), school Pivotal Response Training (Suhrheinch et al., 2020), and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (Grasley-Boy et al., 2020) can strengthen the evidence-based practice of school occupational therapy practitioners and help reduce school’s use of restaint and seclusion. Restraint and seclusion in school can significantly worsen student’s behavioral difficulties (Felver et al., 2016) and negatively impact school climate (Verret et al., 2019).

- Consistently implemented Tier 1 PBIS strategies in alternative education settings for students with serious behavioral challenges decreased incidences of restraints and seclusion (Grasley-Boy et al., 2020).

- Mindfulness movement strategies as a component of trauma-informed teaching and other restraint reduction efforts can significantly reduce the secondary behavioral problems resulting from the use of restraint and seclusion in students with mental health and behavioral challenges (Felver et al., 2016).

- Occupational therapy practitioners provide unique value to school restraint and seclusion reduction efforts for students with mental health challenges through their use of clinical reasoning to integrate ongoing preventative adaptive equipment and techniques into the school environment (Ashburner et al., 2014; Caldwell et al., 2014).

- OT consultation and classroom leadership of brief class room mindfulness and movement break activities can promote ongoing non-violent classroom behavior (Pagano, 2019; Pagano, 2015). Regular mindfulness breaks significantly increased attention in low-income at-risk preschoolers (Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2016) and reduced use of restraint and seclusions in adolescent psychiatric institution students (Caldwell et al., 2014; Felver et al., 2016).

- Sensorimotor-focused treatment strategies can benefit from being integrated into ongoing teaching, socio-emotional and play-based approaches to improve ongoing classroom behavior in students with developmental and behavioral challenges (Soh et al., 2018; Christensen et al., 2020).

References

Ashburner, J. K., Rodger, S. A., Ziviani, J. M., & Hinder, E. A. (2014). Optimizing participation of children with autism spectrum disorder experiencing sensory challenges: A clinical reasoning framework. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81(1), 29-38.

Bazyk, S., Demirjian, L., Horvath, F., & Doxsey, L. (2018). The comfortable cafeteria program for promoting student participation and enjoyment: An outcome study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(3), 7203205050p1-7203205050p9.

Benarous X, Bury V, Lahaye H, Desrosiers L, Cohen D, Guilé JM. Sensory processing difficulties in youths with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2020;11.

Benson JD, Elkin K, Wechsler J, Byrd L. Parent perceptions of school-based occupational therapy services. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2015 Apr 3;8(2):126-35.

Bookheimer SY, Green SA. Associations between physiological and neural measures of sensory reactivity in youth with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2021 Feb 15.

Caldwell, B., Albert, C., Azeem, M. W., Beck, S., Cocoros, D., Cocoros, T., Montes, R., Reddy, B. (2014). Successful seclusion and restraint prevention efforts in child and adolescent programs. Journal of Adolescent Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52(11), 30-38.

Christensen JS, Wild H, Kenzie ES, Wakeland W, Budding D, Lillas C. Diverse autonomic nervous system stress response patterns in childhood sensory modulation. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2020 Feb 18;14:6.

de Korte MW, van den Berk-Smeekens I, Buitelaar JK, Staal WG, van Dongen-Boomsma M. Pivotal Response Treatment for School-Aged Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2021 Feb 9:1-4.

Dellapiazza F, Michelon C, Oreve MJ, Robel L, Schoenberger M, Chatel C, Vesperini S, Maffre T, Schmidt R, Blanc N, Vernhet C. The impact of atypical sensory processing on adaptive functioning and maladaptive behaviors in autism spectrum disorder during childhood: Results from the ELENA cohort. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2019 Mar 13:1-1.

Felver JC, Jones R, Killam MA, Kryger C, Race K, McIntyre LL. Contemplative Intervention Reduces Physical Interventions for Children in Residential Psychiatric Treatment. Prevention Science. 2017 Feb 1;18(2):164-73.

Frolek Clark G, Polichino J. School Occupational Therapy: Staying Focused on Participation and Educational Performance. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2020 Jun 9:1-8.

Grasley-Boy NM, Reichow B, van Dijk W, Gage N. A. Systematic Review of Tier 1 PBIS Implementation in Alternative Education Settings. Behavioral Disorders. 2020 May 4:0198742920915648.

Green SA, Hernandez L, Lawrence KE, Liu J, Tsang T, Yeargin J, Cummings K, Laugeson E, Dapretto M, Bookheimer SY. Distinct patterns of neural habituation and generalization in children and adolescents with autism with low and high sensory overresponsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2019 Dec 1; (12):1010-20.

Oakes WP, Lane KL, Hirsch SE. Functional assessment-based interventions: Focusing on the environment and considering function. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth. 2018 Jan 2;62(1):25-36.

Pagano, J. FAB functionally alert behavior strategies: Integrated behavioral, developmental, sensory, mindfulness & massage treatment. Pagano FAB Strategies, LLC: 2019.

Pagano J. FAB (Functionally Alert Behavior Strategies) to Improve Self-Control. Online Submission. 2015 Mar 1.

Poehlmann-Tynan J, Vigna AB, Weymouth LA, Gerstein ED, Burnson C, Zabransky M, Lee P, Zahn-Waxler C. A pilot study of contemplative practices with economically disadvantaged preschoolers: Children’s empathic and self-regulatory behaviors. Mindfulness. 2016 Feb 1;7(1):46-58.

Slocum SK, Yatros N, Scheithauer M. Developing a treatment for hand clapping maintained by automatic reinforcement using sensory analysis, noncontingent reinforcement, and thinning. Behavioral Interventions. 2021 Feb;36(1):228-41.

Soh, D. W., Skocic, J., Nash, K., Stevens, S., Turner, G. R., & Rovet, J. (2015). Self-regulation therapy increases frontal gray matter in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: evaluation by voxel-based morphometry. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 9, 108.

Suhrheinrich J, Rieth SR, Dickson KS, Roesch S, Stahmer AC. Classroom pivotal response teaching: Teacher training outcomes of a community efficacy trial. Teacher Education and Special Education. 2020 Aug;43(3):215-34.

Verret C, Massé L, Lagacé-Leblanc J, Delisle G, Doyon J. The impact of a schoolwide de-escalation intervention plan on the use of seclusion and restraint in a special education school. Emotional and behavioural difficulties. 2019 Oct 2;24(4):357-73.

Welch, C. & Poltajko, H. J. (2016). This issue is-Applied behavior analysis, Autism, and occupational therapy: A search for understanding. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(4), 7004360020p1-7004360020p5.

Wyman J, Claro A. The UCLA PEERS school-based program: Treatment outcomes for improving social functioning in adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder and those with cognitive deficits. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2019 Feb 28:1-4.